In recent years there has been something of a revival of ‘nose-to-tail’ cooking. The idea is simple. It begins with the observation that we have become accustomed to eating only those carefully prepared and packaged parts of the pig, cow or lamb that you can find on supermarket shelves. Smoked bacon. Ribeye steak. Lamb chops.

(Of course, we do already eat the off-cuts, but only in the more acceptable form of sausages, burgers, and meatballs. But this does not count as nose-to-tail cooking, since you literally have no idea what you’re eating, as proved by the great horse scandal of 2013.)

Clearly, in the age before supermarkets and the sanitised privileges of a consumeristic age, no part of the animal was wasted. This is quite obvious if you have ever experienced a food market outside the Western world where baskets of goats heads peer at you, alongside buckets of pigs trotters. Just about every part of the animal can be eaten, if prepared in the right way. Nothing is wasted and everything is useful.

This rediscovery of the potential in bone marrow and cow tongue has led to a revival of cooking every part of the animal – nose-to-tail – that has begun to affect how we think about our relationship with the dead creatures we eat. (Ironically, this movement has not sprung from economic need, but rather from the privileged and newly gentrified haunts of the East London food scene.)

I find this a compelling analogy for the state of preaching today. The growth of consumeristic culture in the West, along with pastoral ambition to appear successful, has applied market pressures to create churches perfectly designed to cater to an audience. Just as the gore of the slaughterhouse has been replaced by the polish of the plastic-wrapped packages on supermarket shelves, with neatly and finely sliced portions of tender cuts to feed the masses, so we have seen this reflected in churches, particularly in preaching. This takes the form of the short preaching series, exclusively focussed on ‘how to’ questions – easily purchased and digested by the hungry consumers. There is nothing there to really challenge the worshiper; no bones or tough cuts that need more mastication. Instead, spiritual food is doled out with step-by-step instructions, and crucially, without blood.

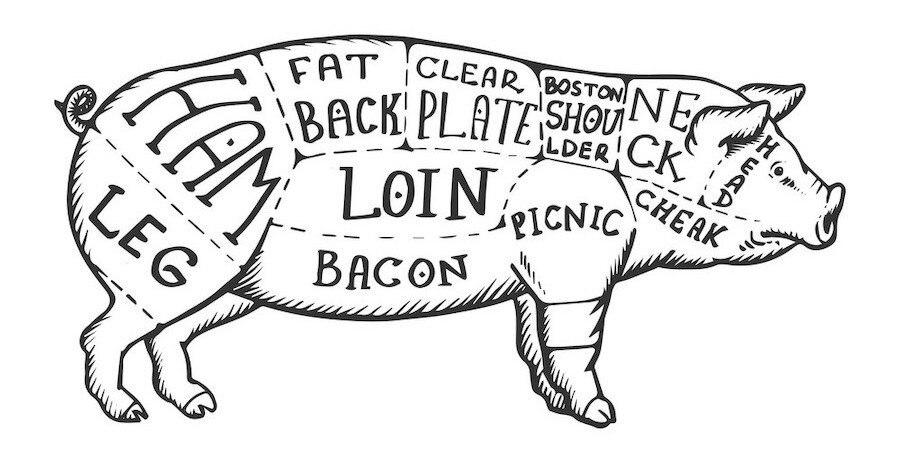

One of the reasons I am a strong advocate for careful expository preaching is that it forces you as a preacher to offer people a nose-to-tail diet. This is very challenging for you and for the congregation. You take a book of the Bible and then you get to work like a skilful butcher. But if you are really an expositor, then you are not permitted to extract only those portions that are most easily prepared, chewed and digested; rather, in true expository preaching you aim to miss nothing of what God decided to include in his most Holy and Infallible Word.

So, one week you encounter an ear or a tail or a digestive tract. And at that point you have to think very carefully about how you will prepare this portion for consumption. You have to resist the temptation to simply discard the meat (by ignoring the passage), or to grind it up into sausages (by dealing with it very superficially, or mixing in an excessive ratio of herbs and bread in the shape of stories and practical points, so that the passage is basically unrecognisable). Now, it is true that any good chef must find a way to make an ear or entrails more appetising, and any good preacher must find a way to make a text ready for consumption. But still, there’s a sense in which the people need to encounter these awkward and offensive parts of the Bible, or else they remain juvenile, only ever capable of eating breaded meat with lots of ketchup.

Why is this so crucial? I believe that consumeristic Christianity has managed to survive because the conditions have been favourable. Broadly speaking, it has been possible to offer people a stripped back and simplified spirituality that has sat comfortably with people going about their normal lives. Drive-thru church gives a boost each week and helps people to stay positive and feel spiritual.

But times are a-changing. The view of what is morally normal and acceptable has so shifted in recent years that it is no longer possible for consumeristic churches to produce Christians that can survive in this modern world. A normal Christian (by New Testament standards) is basically a fanatic and a bigot in today’s world. And so, we are increasingly identifying with the experience of being ‘sojourners and exiles’, as Peter described in his first letter.

In this age, some well-meaning pastors will continue to serve up easily digestible ‘content’ (a word that perfectly captures the spirit of the age) in the naive assumption that the Holy Spirit will make up for what’s lacking, and mature disciples will emerge without the need for discomfort on a Sunday. But sadly, all this will create is Christians with no moral fortitude or conviction who will be crushed by the onslaught of lies that our culture is offering up.

More sobering still, we see that other pastors will continue to deliberately create a highly processed and refined product to pitch to their spiritually obese audiences – churches that want to be known for what they are for, rather than what they are against (as though these two things do not go together). But, by slicing away and discarding even more aspects of the truth that are considered offensive, reducing the diet down to the spiritual equivalent of chicken nuggets, the sad result is that underneath the polished appearance of the slick establishment, these churches will be rat- and cockroach-infested havens for sin.

The only alternative is Spirit-empowered and bold nose-to-tail preaching of God’s word. Now, more than ever, we need to recover a conviction that all of God’s word is useful ‘for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work’. I believe this is the only way to form disciples capable of weathering the storm that is coming and even now is upon us.